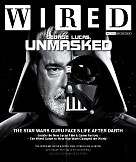

Adding to my 'Cinematic Sprit & Soul' blog below, Rohne & I also waxed lyrical on Star Wars - my excitement focusing from a piece in this month's Wired with Lucas on the cover.

Like John Landis slipping in the quick 'See You Next Wednesday' line in all his movies (presumably wordplay on 'C.U.N.T'!), Lucas has often given a healthy nod to Arthur Lipsett's '2187', check this, I love it! (from Wired 13.05):

"The film that made the most profound impression on Lucas, however, was a short called 21-87 by a director named Arthur Lipsett, who made visual poetry out of film that others threw away. Working as an editor at the National Film Board, he scavenged scraps of other people's documentaries from trash bins, intercutting shots of trapeze artists and runway models with his own footage of careworn faces passing on the streets of New York and Montreal. What intrigued Lucas most was Lipsett's subversive manipulation of images and sound, as when a shot of teenagers dancing was scored with labored breathing that might be someone dying or having an orgasm. The sounds neither tracked the images nor ignored them - they rubbed up against them. Even with no plot or character development, 21-87 evoked richly nuanced emotions, from grief to a tenacious kind of hope - all in less than 10 minutes.

Lucas threaded the film through the projector over and over, watching it more than two dozen times. In 2003, he told directors Amelia Does and Dennis Mohr, who are making a documentary on Lipsett, "21-87 had a very powerful effect on me. It was very much the kind of thing that I wanted to do. I was extremely influenced by that particular movie." Deciding that his destiny was to become an editor of documentaries who, like Lipsett, would make avant-garde films on the side, Lucas worked in the USC editing room for 12 hours at a stretch, living on Coca-Cola and candy bars, deep in the zone.

"When George saw 21-87, a lightbulb went off," says Walter Murch, who created the densely layered soundscapes in THX 1138 and collaborated with Lucas on American Graffiti. "One of the things we clearly wanted to do in THX was to make a film where the sound and the pictures were free-floating. Occasionally, they would link up in a literal way, but there would also be long sections where the two of them would wander off, and it would stretch the audience's mind to try to figure out the connection."

To simulate a realistic society of the future on a shoestring budget for THX, Lucas and Murch pushed that audiovisual disconnect as far as they could. A scene in which the hero (played by a young Robert Duvall) is tortured is made more horrific by the banal shoptalk of his offscreen tormentors; the chatter of unidentified voices throughout the film reinforces the idea that in a world of ubiquitous surveillance, you are never alone.

Lucas never met the young Canadian who influenced him so deeply; Lipsett committed suicide in 1986 after battling poverty and mental illness for years. But like a programmer sneaking Tolkien lines into his code, Lucas has planted stealth references to 21-87 throughout his films. The events in the student-film version of THX took place in the year 2187, and the numerical title itself was an homage. In the feature-length version, Duvall's character makes his run from a subterranean city when he learns that the love of his life was murdered by the authorities on the date "21/87." And in the first Star Wars, when Luke and Han Solo blast into the detention center to rescue Princess Leia, they discover that the stormtroopers are holding her as a prisoner in cell 2187.

The rabbit hole goes even deeper: One of the audio sources Lipsett sampled for 21-87 was a conversation between artificial intelligence pioneer Warren S. McCulloch and Roman Kroitor, a cinematographer who went on to develop Imax. In the face of McCulloch's arguments that living beings are nothing but highly complex machines, Kroitor insists that there is something more: "Many people feel that in the contemplation of nature and in communication with other living things, they become aware of some kind of force, or something, behind this apparent mask which we see in front of us, and they call it God."

When asked if this was the source of "the Force," Lucas confirms that his use of the term in Star Wars was "an echo of that phrase in 21-87." The idea behind it, however, was universal: "Similar phrases have been used extensively by many different people for the last 13,000 years to describe the 'life force,'" he says.

The lessons Lucas learned from filmmakers like Lipsett, McLaren, Jutra, and Kurosawa helped shape the creation of all of his later work. "My films operate like silent movies," he explains in an unused portion of an interview for a documentary on editing called Edgecodes.com. "The music and the visuals are where the story's being told. It's one of the reasons the films can be understood by such a wide range of age groups and cultural groups. I started out doing visual films - tone poems - and I move very much in that direction. I still have the actors doing their bit, and there's still dialog giving you key information. But if you don't have that information, it still works."

Rounding off Star Wars tings, check people queuing for the Sith, 360 visuals - flip da pic!!!

© 2005 Green Bandana Productions Ltd. Website design by Steve Mannion.